Story

Customizing Learning through Technology

DATE

December 22, 2019

By Andy Steiner

Two years ago, Watertown High School began offering some of its students a chance to customize what they studied and to set their own pace of learning. Principal Mike Butts is leading the school’s customized learning program, but he credits another organization in South Dakota’s education ecosystem — Technology and Innovation in Education (TIE) — for the early thought leadership that made the program possible.

“TIE is leading the customized learning movement in South Dakota,” Butts says. “It brought together the think tank of education leaders that developed the program and today trains teachers at customized learning programs across the state in how to ensure students succeed.”

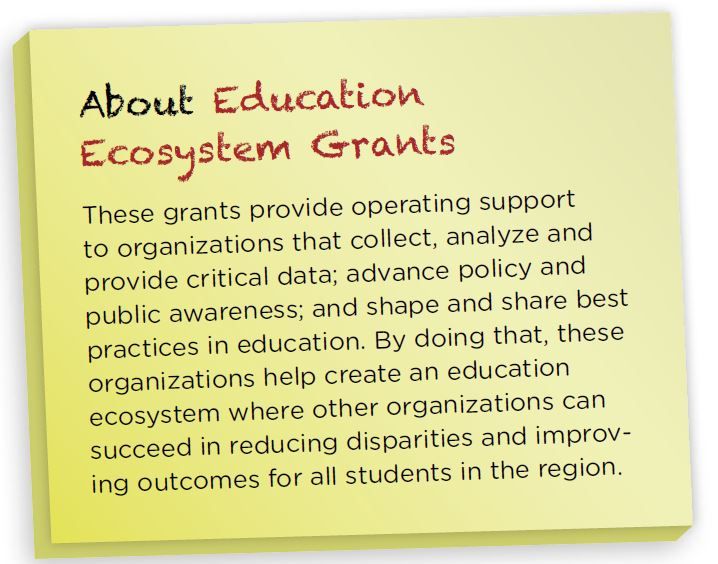

It’s because of work like this to improve the education ecosystem that TIE and 11 other organizations are inaugural recipients of 2014 Education Ecosystem Grants.

Julie Mathiesen (BF’03) is TIE’s director. She came to her current work at TIE through the classroom as an art and biology teacher. In the classroom, she says, “technology created more engagement with my students. It allowed them to pursue content of interest in a way that was more student-directed and less teacher-directed, and it freed up my time to work one-on-one with students who needed extra help and support.”

Mathiesen’s skills at merging technology with education eventually brought her to TIE, where she leads efforts to teach South Dakota educators about the benefits of creating modern information-age classrooms where learning plans can adjust to meet the unique needs of individual students. Enabling technologies allow for a shift to more customized and personalized education. By moving away from a one-size-fits-all, time-based, batch processing mode of education, schools can reach more children at their skill and interest level. And performance-based, student-paced education increases student agency and success.

The Education Ecosystem Grant to TIE “helps us spread these ideas and build this capacity in schools so they can engage in more customized learning for students,” Mathiesen says. “We have pieces of these ideas and technology established around the state, but we need a more organized leadership to record that information, share it, and help grow and disseminate it within all schools in South Dakota.”

TIE is a component of Black Hills Special Services Cooperative, an agency that advances public education and technology in the state’s rural communities. Joe Hauge, the Cooperative’s executive director, says that TIE, which began some 30 years ago as a way to distribute computer technology and training to South Dakota schools, continues to live out that mission as it helps educators across the state make the transition to customized learning.

“With the Bush Foundation dollars, we’re just starting to see the first steps happen,” Hauge says. “We’re reporting best practices. We’re learning from each other. At the end of a couple of years, we will have this concept really ingrained in schools across the state.”

Mathiesen is excited by the promise of this new way of learning and teaching. “My work at TIE is really my dream job,” she says. “It is about helping teachers make teaching more relevant for students by showing them how to improve the learning experience through technology.”

Great Teachers Great Minds

Even before there was a Bush Foundation, Archibald Bush invested in education, through supporting both individuals of promise and educational institutions.

Continue reading

-

News

Power of Bridging event

Mark your calendars for a special community event with john a. powell! Thanks to our friends at MPR News, we'll be hosting john at the Fitzgerald Theater on December 2 and hope you can join us!

-

News

Celebrating the 2025 Bush Prize honorees

Learn more about the 2025 Bush Prize honorees who are helping to make our region better for everyone!

-

News

Welcome to new Bush staff members

We are celebrating some new Bush colleagues and hope you get to meet them soon!