Story

What Would Love Do?

Amelia Franck Meyer (BF’15) is transforming the child welfare system by healing trauma and putting families first

Amelia Franck Meyer (BF’15) radiates an unwavering clarity of purpose: She knows in her bones that she was born to be a social worker.

From working in individual group homes to leading regional agencies, her entire working life has been dedicated to improving the well-being of children in foster care. As her leadership journey has evolved, so has the scope of her ambition. Her goal now is nothing less than a total reinvention of the American child welfare system, which she believes will in turn positively impact societal challenges ranging from incarceration to homelessness to health care. In Meyer’s view, mitigating and healing childhood trauma is the first critical step to transforming the world.

Those who know her are placing their bets on Meyer achieving her goal, describing her as a uniquely driven, passionate and visionary leader. Even People Magazine has taken note of her work, naming her one of People’s 25 Women Changing the World in November 2018. As her friend and mentor Trudy Bourgeois, a leadership strategist and coach, says, “Amelia was sent to change the child welfare system. With great people, history chooses them. They don’t choose their dream; the dream chooses them, because they’re the one equipped to bring it to reality. That’s what she is going to offer the world.”

Family as Protective Charm

Meyer’s path to becoming a system-rocking social worker began in her childhood home in a troubled neighborhood outside of Chicago. Meyer grew up with her parents and four siblings in an upstairs two-bedroom apartment; her paternal grandparents lived downstairs. “We were taught never to be alone with my grandpa,” Meyer says. “We didn’t know it at the time, but my grandpa was a pedophile and had horrifically abused my dad, who was bipolar. My dad suffered from depressive episodes and was unemployed a lot. He had been so traumatized, he had trouble functioning and couldn’t move out of the house. His abuser lived right downstairs.”

Outside Meyer’s childhood home, the neighborhood teemed with violence, gang activity, drugs and alcohol. But amidst the dangers just outside the family’s small apartment, Meyer’s parents provided a safe, warm and loving home for her and her brothers and sisters. “Our house was the

house everyone came to,” says Meyer.

She and her family spent weekends camping and playing games around the fire. Her maternal grandparents made sure they always had food in the house, dropping off groceries on a regular basis.

Her father volunteered at a local Catholic school running bingo and serving as school board president, which allowed Meyer and her siblings to attend the school for reduced tuition. She became the only one of her neighborhood friends to graduate from high school (ranking third in her class) and the only one who didn’t have a child before her 18th birthday.

“My siblings and I were very tight, very close with our family. That was protective for me against everything else that was going on in the community,” says Meyer. She thinks of her parents as having been “closet social workers,” who instilled in her a mindset that there is always someone worse off than you are. Despite her dad’s lowered capacity to work, both parents modeled a regular practice of volunteering, donating and caring for others in the community. All these things, combined with the poverty and mental health-related challenges she witnessed in her own home and neighborhood, added up to Meyer’s sense of her future calling. “I was destined to be a social worker,” she says.

At Illinois State University (ISU), Meyer majored in psychology with a minor in human biology, a combination that gave her an understanding of people both inside and out. This passion for understanding and empathizing with people has informed and motivated her work ever since.

A Calling is Born

After getting her degree in psychology, Meyer worked as an admissions counselor at ISU for a couple of years before entering the master’s program there in sociology/marriage and family. During her time in admissions, she shared a small office with Steve Smith, now CEO of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. Smith and Meyer have remained friends. In recent years, they’ve formalized their professional relationship, coaching and supporting one another. “I describe Amelia as a force of nature,” says Smith. “She’s always been highly intelligent, compassionate, driven and resourceful. She’s also a learner.”

After completing her first master’s degree at ISU, Meyer began working in group homes for children in Illinois, where she was confronted for the first time with the plight and challenges faced by kids in the American foster care system. “I was finding that these kids were untethered; they belonged to no one,” she remembers. Disturbed by the institutional atmosphere of the homes and the rules and regulations that governed them, Meyer did her best to create a warm and supportive environment in the homes where she worked, rather than one of punishment and control. “A mentor at the time told me, ‘If you treat people like animals, they’ll act like animals. We need to create environments that are human.’”

So, Meyer organized movie nights with popcorn, made special treats and recipes that her mom used to cook for her and her siblings, hung art on the walls, took the kids on trips into the community that she dubbed “family vacations” and tried to nurture a sense of belonging among all the home’s residents.

“Humans don’t do well when they’re untethered,” says Meyer. “I come from a sociobiological perspective that asks, ‘What do humans need to thrive?’ I’m so clear on that: You need a single nurturing protector for your whole life. Someone who has your back. When we remove kids from their families, we untether them. When that happens to you, you push everyone away because you don’t know who to trust.”

When the agency that Meyer was working for in Illinois went through a challenging merger, she decided to move. After visiting a friend in Minneapolis and interviewing with a few organizations, she moved to Minnesota in 1998 to work in deaf-blind services and pursue a Master of Social Work at the University of Minnesota. In 2001, she was offered a position leading PATH Wisconsin (now Anu Family Services), a child welfare agency that serves Wisconsin and Minnesota. In her interview with the board, she told them, “If you’re hiring me to put more kids in more foster homes, you have the wrong person. But if you want someone to transform the system, then hire me.”

Between her time working in group homes and her extensive academic studies into the physical and emotional requirements for human thriving, Meyer had developed a clear view of the broken aspects of the child welfare system, as well as what was needed to fix it. She was ready to get to work.

“Impact is my middle name”

When Meyer started at Anu in 2001, she launched a national research project to determine the permanency rates achieved by top-performing agencies in the country (the rates at which foster children are placed with legally permanent families, whether through reunification with birth families, adoption or guardianship by relatives). The research showed that, nationwide, only 30% to 40% of children were placed in permanent homes after being in foster care, with top-performing agencies maxing out at around 45%.

About 650,000 children spend time in foster care each year and approximately half of them are placed with strangers. Once within the foster care system, children are moved from family to family an average of once to twice every year. According to Meyer, this separation of children from the only family they know (even if that family is abusive or neglectful) and the subsequent pattern of being whisked from home to home represents a psychological trauma.

“We must be part of a human family, part of a tribe, in order to feel safe and protected,” she explains. “When children don’t feel claimed, they go into survival mode. They’re hyper-aroused, looking at everything and everyone as a threat. They lose the ability to relax, to think, to learn. And they lose the ability to connect and trust other people because they’re so profoundly consumed with their own survival.”

This foundational attachment trauma is predictive of future problems ranging from addiction to depression to chronic disease. “The pain of not belonging, that profound loneliness, is so significant that people will use drugs and alcohol to numb it,” says Meyer. “They may fall into despair or become so completely numb that they disconnect from all humans and become capable of the kind of violence we witness on the news every night.” And this kind of trauma is cyclical, spiraling down through generations. Young women in foster care are more than twice as likely as their peers to get pregnant before the age of 19, while also facing a greater likelihood of homelessness, incarceration, PTSD, depression, anxiety and addiction, all of which set them and their offspring up to repeat the cycle of entering the child welfare system.

“Every child on the planet needs their mom in order to be OK, and if not mom then dad, and if not dad then a single nurturing caregiver,” says Meyer. “But we do nothing to help the mamas. We punish them.”

“If you’re hiring me to put more kids in more foster homes, you have the wrong person. But if you want someone to transform the system, then hire me.”

Meyer contends that this cycle of punishment and removal perpetuates the same traumas that lead caregivers to abuse and neglect kids in the first place. Those who suffer the childhood trauma of being abused, neglected and removed from their families grow up unable to connect. When they become parents themselves, they don’t have the emotional and psychological resources to parent well. And the pattern repeats: The system steps in to remove the child and punish, blame and shame the parent. “At that point it’s almost impossible to fix the situation because the parent has received the mortal wound of having their kid removed,” says Meyer. “Odds are good they’re going to have another kid to fill that hole.”

A difficult truth: Children left in abusive and neglected environments tend to fare better than those who enter foster care. Studies have shown that maltreated youth who are left in their own homes are far less likely to become pregnant as teenagers, less likely to wind up in the juvenile justice system and more likely to hold a job for at least three months than comparably maltreated children placed in foster care. “The cure is worse than the disease,” says Meyer. “We can’t leave kids alone to fend for themselves, but what we’re doing is making it worse.”

At Anu Family Services, Meyer and her staff set an audacious goal of achieving a 90% permanency rate. “We believe that all youth deserve and can have permanent families, but we know some kids have such significant relational trauma that they might initially need more restrictive care [such as group homes or residential treatment facilities] to keep them safe while working to heal that trauma,” says Meyer, explaining that she and her team estimated that 90% of the time, emotional and logistical support for families could make permanent placement safely possible. With this goal in mind, they set out to form partnerships and consult with field experts and authors whose models they wanted to put into practice.

In 2008, Anu partnered with the University of Minnesota on a pilot program that utilized a model of family search and engagement to identify loved ones with whom foster youth had lost contact. Though the agency approached the pilot with great clinical practice and preparation, it was not a success.

Meyer tells the story of one child from the pilot who had been in eight foster homes over the course of five years. “We found his uncle in less than a month of searching,” remembers Meyer. “He was wealthy and he wanted this child. He had called the county but couldn’t find any information.” Anu hosted a family reunion for the child and his uncle at the farm where the child was staying. After his uncle left the party, the celebratory vibe quickly faded when the boy went out back and gutted a cow wide open. “The child was enraged and rightfully so,” says Meyer. “If his uncle wanted him, why hadn’t he found him? If we knew how to find his uncle in a month, why had he gone through five years of foster care?”

Other youth in the pilot program lashed out in similarly violent ways following positive reunions with their lost relatives. This pilot program, disappointing as it was, yielded a key insight that became Anu’s “golden nugget of truth”: A normal, natural response to being disconnected is a diminished capacity to connect. “If you went home and found your spouse in bed with your best friend, you’re not going to approach your next partner with a lot of trust,” says Meyer. “That’s a normal response, to disengage the part of yourself that openly and freely gives and receives love.”

This insight led to innovations that held the key to greater success. By late 2012, Anu had increased its permanency rate to 70%, nearly double the 38% rate when Meyer joined the agency. This impressive gain came through the implementation of transformative innovations such as Intensive Permanent Services, in which specialists worked one-to-one with youth over the course of 9 to 24 months to build trust, and the 3-5-7 Model, a practice based in knowledge of how trauma works, to help youth understand their past, grieve losses and prepare for permanence. Through Anu’s family search and engagement efforts, staff were able to find connections that were lost as a result of multiple foster placements, including family members, relatives, former foster parents, teachers and coaches, who were then enlisted to become a concrete support network for the youth.

By 2013, all of the youth who participated in Anu’s Intensive Permanence Services for 10 months or longer showed an increase in the quantity and quality of their connections. “We used to think that kids who were attachment disordered would be that way for the rest of their lives,” says Meyer. “I knew we had to find a way to heal that. The part that’s magical about the model we used is the continuity of relationship — someone standing with you and saying, ‘I’m going to walk with you through this until you come out the other side. Your pain doesn’t scare me. You are worthy of my time and I will persist with you until you feel better.’”

This novel approach to disrupting the child welfare system earned Anu Family Services a Bush Prize for Community Innovation in 2013. But Meyer knew that it couldn’t be just the kids lucky enough to be referred to Anu who got to reap the benefits of their methods. She began thinking bigger. “I felt like we had the cure for cancer, but we couldn’t get it to the kids,” she remembers. “I wanted to change the whole system.”

Reimagining the Child Welfare System

In addition to her work at Anu Family Services, Meyer began looking for trailblazers, disruptors and innovators across the child welfare system. In 2015, she partnered with Chuck Price, director of health and human services for Waupaca County in central Wisconsin, to help him and his team radically overhaul the county’s child welfare services. “Amelia causes you to question everything you’re doing, while also validating the steps you’re taking,” says Price. “She helped us focus on the notion that no child should be placed with a stranger and that our whole lens should be on how we can mitigate further traumas. She also helped us establish a culture and environment where people want to work, so we have less turnover. Amelia is infectious — you can’t help but want to go do something after spending time with her.”

Today, Waupaca County has decreased the number of children in out-of-home care (whether group homes, foster placement, detention or shelter facilities) by 17%, has moved 25% of its budget into prevention services, has trained 100% of its staff in trauma-informed care and has a turnover rate of less than 6% (compared to a national average of 30% in the child welfare system). Like Meyer, Price is committed to not just tweaking the system as it currently exists, but fundamentally reinventing it. “We didn’t get the light bulb by continuously tweaking the candle,” he notes. “It’s going to take too long to fix the system as we know it today. We are going to come up with a different way that makes this archaic system obsolete.”

Meyer’s burgeoning efforts to fundamentally change the child welfare system put her on the radar of Jen Aspengren, at the time a member of the Venture and Fellowship team at Ashoka United States. Ashoka is a community of social entrepreneurs that supports changemakers, and in 2014, they awarded Meyer an Ashoka Fellowship. “Amelia had taken some of the most innovative ideas across the country and put them together to put kids at the center,” Aspengren says. “But one area where she needed to grow was in understanding that she can’t do it alone. She’s since grown to be able to think large-scale about how to bring a whole system along in wanting to change itself.”

By 2015, Meyer had grown increasingly restless leading a direct service organization. In her application for a Bush Fellowship, she wrote, “It is time to make the system my client. I have never been more sure of my life’s purpose.” She was awarded the Fellowship in May 2015, around the same time she began convening think tank sessions with her “personal board of directors,” 15 to 20 people from across the child welfare space who were interested in seeing — and driving — a change. The outcome of these sessions was Alia Innovations, a nonprofit consulting team which Meyer founded in December 2015 with a goal of transforming all organizations across the country that are entrusted with the welfare and well-being of children. In July 2016, Meyer left Anu Family Services to focus on running Alia Innovations full time.

“It was really the connection with other Bush Fellows that helped me be brave enough to do that,” says Meyer. “I resigned from my job of 15 years to start something that I didn’t know if I could fund, while I was getting my doctorate. Launching a new organization, pursuing the Fellowship and the doctoral program all at once — that was quite a year.”

Meyer started thinking deeply about what she needed in order to sustain herself for the long haul in tackling these substantial challenges. “A big focus of the Bush Fellowship is on helping you take care of yourself,” she says. “I started a daily practice of keeping a gratitude journal, which helps reframe the way you think about things. Bad things happen every day and so do good things, so what’s your mindset? I started really focusing on relationships and dug in deep with the people close to me. I sustained myself on the love of that inner circle while doing these hard things.”

In order to fulfill Alia’s transformative mission, Meyer knew she needed additional expertise in organizational development and change processes. The Bush Fellowship allowed her to enroll in a doctorate program in organizational change and leadership at the University of Southern California. The program led her to connect with Annette Diefenthaler of IDEO, a global design company committed to creating a positive impact. Meyer had a vision for bringing together leaders, movers and shakers from child welfare and human services to imagine a different future together. She knew IDEO could help.

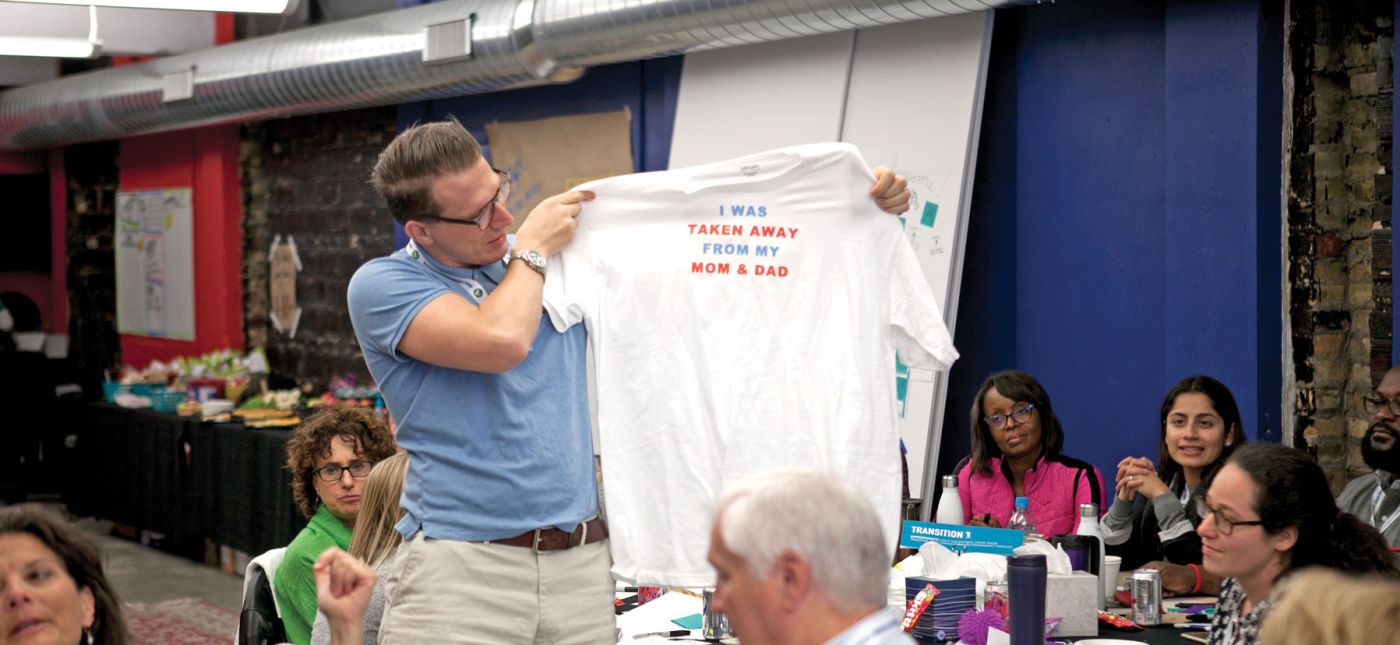

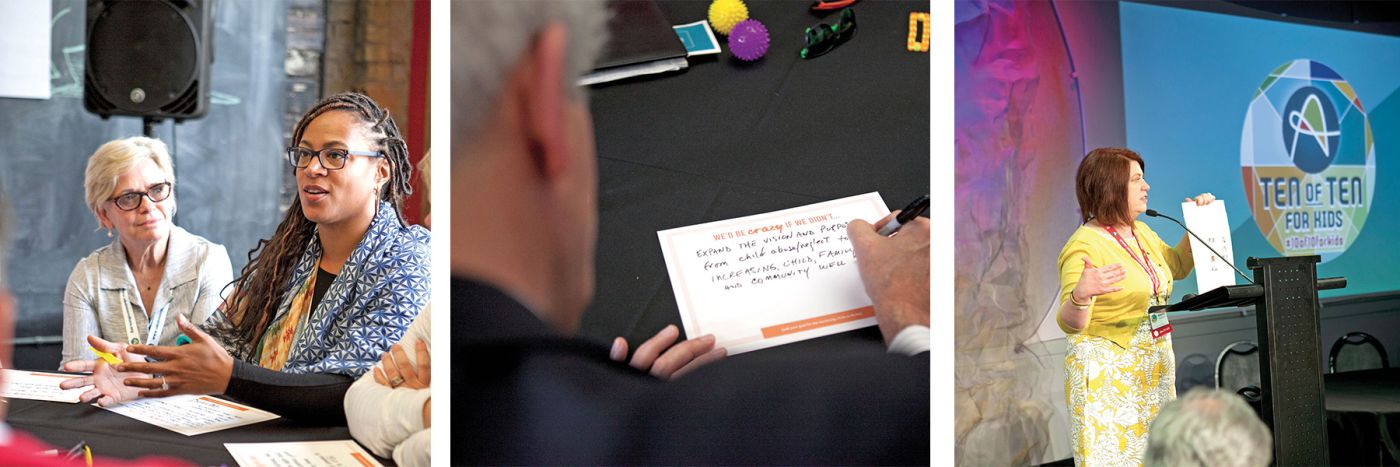

“Amelia first called in October 2016,” says Diefenthaler. “What stuck out was her clear vision of what she wanted to achieve. She had such an unwavering commitment to making change and we found that impressive.” Diefenthaler and her colleagues at IDEO worked with Meyer over the course of several months to design an event called Ten of Ten for Kids, a three-and-a-half-day conference at which 10 groups of 10 people from every facet of the child welfare sector came together to apply design-thinking principles and imagine new ways forward.

“Going into the event, we knew we weren’t going to reinvent child welfare in a few days,” says Diefenthaler. “But what we learned was the wishes and aspirations that people had and what ideas were already out there that could be built on. The principles we established at that event became the foundation of what Alia Innovations now does.”

Of the 100 participants at Ten of Ten for Kids, 30% had lived experience of being a child in the foster care system. Among them was Shenandoah Chefalo, author of Garbage Bag Suitcase, a powerfully written memoir of Chefalo’s childhood with abusive and neglectful parents and her ensuing journey through the child welfare system. For Chefalo, the introduction to Meyer and Alia Innovations through Ten of Ten for Kids felt providential. “I’ve been with them ever since,” says Chefalo, who now works as a guide with Alia’s UnSystem Innovation Cohort — a team of innovative individuals committed to leading six agencies through a three-year cultural transformation.

“We can’t simply tweak things and expect it to get better,” stresses Chefalo. “But these six agencies around the country are trying to be innovators and they’re getting pushback.” A fear of kids getting hurt is at the core of the child welfare system, driving nearly everything it does. “People within the system are looking for solutions, but they’re risk averse,” explains Aspengren, who now serves on Alia’s board of directors. “No one wants a child to be hurt or killed on their watch, so the tendency is to move kids the moment there’s any potential for harm — which ends up doing absolute harm, by severing those ties and retraumatizing them. You’re trading large potential harm for finite absolute harm. Shifting that is the biggest challenge.”

For Chefalo, the need for change is visceral and personal. “At 13, I couldn’t see my mom’s pain. I didn’t understand why she was using drugs and had disappeared,” says Chefalo. “No one helped her; she was just deemed a bad mom. What if she had been given tools to heal her own trauma instead of separating us? I’m now in my 40s and I’m still trying to deal with the stuff that happened to me as a kid and grapple with how it’s affected my own parenting.”

Do What Love Would Do

The need for healing — for grace, forgiveness and tenderness — persists throughout the child welfare system, from parents and caregivers to children, to the caseworkers and administrators tasked with managing care and placement. “We have an ethical responsibility to ensure that our child welfare system is well enough to heal, or it will propagate further damage and unhealth,” says Meyer, who has made stabilizing the emotional well-being of those who work in child welfare a cornerstone of Alia’s work. “Our nation’s youth can only heal if their healers are well. Getting them to a place of stability allows them to help others.”

She points to the fact that the greatest predictor of whether a child achieves permanency or not is the number of different caseworkers they have over the course of their time in the system. As caseworkers burn out and leave the field, the kids left behind fare worse and worse. Practicing self-care allows those working within the system to stay engaged.

“Alia does an amazing job of modeling the self-care they’re promoting across the system,” says Aspengren. “They know they’re doing hard work and they need balance in order to do it.” Meyer has an absolute commitment to getting enough sleep, and she says she’s given up baking for her kids’ school fundraisers (as well as the guilt that comes with saying no). “I’ve given up feeling bad,” she says. “I’ve given up shame. I focus on good enough.” She also credits her husband Mark with being an amazing source of emotional and spiritual support for her and their five kids. Staff at Alia are encouraged to take “well days” — days when they can practice self-care in advance of getting sick in order to keep themselves balanced and healthy. They foster a culture of deep listening and support and create a caring environment where people feel connected and work to sustain themselves and each other.

For Meyer, it all comes down to a core commitment to love. One of the guiding tenets at Alia is nurturing the capacity for joy, with the understanding that the ability to express and experience joy is a fundamental measure of well-being. “When in doubt, do what love would do,” says Meyer, pointing to the sign hanging in Alia’s office where that phrase dominates the list of Alia’s organizational principles. “Do what you do for someone you love. It’s not that hard.”

Tackling Systemic Change

There are some universal challenges faced by individuals trying to drive bold systemic change — challenges that the Bush Fellowship program is designed to help grantees confront.

“We look for how we can help people get outside their current mental models,” explains Anita Patel, leadership programs director at the Bush Foundation. “We ask Fellows what might feel scary that they know they need to reach for, or what they need to heal within themselves to open up to new ideas. Part of our work in helping these leaders who are already doing amazing things is to look at what it would take for them to create change for all people in our region.”

Fellows are also encouraged to examine their own stories and heritage in order to strengthen their ability to interact across differences, and to consider how others experience their leadership. “Systems are made of people,” says Patel. “When we think about systems change, we’re fundamentally talking about human interaction.”

Every Fellow has a leadership coach who, in addition to challenging the Fellow to grow, helps them celebrate their existing skills and accomplishments as a leader. Coaches also nurture balance and self-care in Fellows, coaxing them to hold responsibility and possibility in ways that drive them but also help them stay healthy.

The Fellowship also fosters connections among the Fellows themselves. “These connections with each other help them to think differently and get outside of their particular expertise or usual way of being,” says Patel. “Maybe someone working to transform education needs to connect with someone in the arts or the business community to spark new ideas and connections.”

Ultimately, the Bush Fellowship provides a unique combination of important resources for leaders to grow. “It’s money, yes, but it’s also time, connection and confidence,” adds Patel. “And it’s not prescriptive. Grants are often predicated on a need for a specific outcome. The Bush Fellowship is about who are you, how you want to grow, the change you want to make in yourself and the community, and giving you what you need to make that happen.”

Continue reading

-

News

Power of Bridging Event

Mark your calendars for a special community event with john a. powell! Thanks to our friends at MPR News, we'll be hosting john at the Fitzgerald Theater on December 2 and hope you can join us!

-

News

Celebrating the 2025 Bush Prize honorees

Learn more about the 2025 Bush Prize honorees who are helping to make our region better for everyone!

-

News

Welcome to new Bush staff members

We are celebrating some new Bush colleagues and hope you get to meet them soon!